Yonas Adaye Adeto is Director of the Institute for Peace and Security Studies (IPSS) at Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. He obtained his Ph.D. from the University of Bradford, UK, and is an Assistant Professor of Peacebuilding and Security Governance in Africa.

Abstract

Scholarship on the challenges of ethno-linguistic federalism in contemporary Ethiopia is copious; yet a critical analysis of violent ethnic extremism in the country and its implications for the sub-region is rare. This article argues that violent ethnic extremism is a threat to the existence of Ethiopia and a destabilising factor for its neighbours. Based on qualitative empirical data, it attempts to address the knowledge gap and contribute to the literature by examining why violent ethnic extremism has persisted in the post-1991 Ethiopia and how it would impact on the stability of the Horn of Africa. Analysis of the findings indicates that systemic limitations of ethno-linguistic federalism; unhealthy ethnic competition; resistance of ethno-nationalist elites to the current reform; unemployed youths; the ubiquity of small arms and light weapons; and cross-border interactions of violent extremists are the major dynamics propelling violent ethnic extremism in Ethiopia. Thus, Ethiopia and the sub-region could potentially face cataclysmic instabilities unless collective, inclusive, transformative and visionary leadership is entrenched.

1. Introduction1

Violent ethnic extremism is a threat to the existence of a contemporary Ethiopian state and a destabilising factor for the Horn of Africa. Literature indicates that the greatest risks of starting future wars will likely be ethnicism and the new nationalism that seems to be on the rise in many parts of the world in the 21st century (cf. Barton and Carter 1993:555–556; Mishra 2017:270; Binik 2020:91). While violent extremists2 kill fewer people than traffic accidents3 or diabetes4, they often target civilians, and pose grave challenges to human rights and dignities, and the security and well-being of individuals. As a strategy, extremism is invariantly adopted by intolerant actors who do not believe in dialogue, negotiation or discussion as ways of dealing with differences of ideas in a civilised manner (Berman, Eyoh and Kymlicka 2004:6; Appiah 2018:50). The only way for them to succeed is by terrifying innocent civilians (Rogers 2016:5; Harari 2018:161; Diamond 2019:390). In this way the potent perception is created that violent extremism (which takes different forms in different contexts, e.g. religious, ethnic, right wing) is a subversion of established political processes, and that a violent action can induce a change in the political situation by spreading fear (Mishra 2017; Binik 2020:13). The severe dangers of violent extremism, rendered as ethnic extremism in the contemporary Ethiopia, are ripping the society apart, with far-reaching consequences to the stability of its neighbours (Lyons 2019:123).

Studies on the challenges of ethno-linguistic federalism in Ethiopia abound; however, little has been done to translate this understanding of the systemic challenges and implications into a comprehensive analysis of the violent ethnic extremism in the country and the sub-region. The present study, therefore, aims to address the existing empirical research gap and contribute to the academic literature. To this end, it first sets out the scene of the research context; second, it provides a conceptual framework of violent ethnic extremism, which is followed by an outline of the research findings; it then identifies and critically analyses the drivers and enablers of ethnic extremism in post-1991 Ethiopia with its implications for the stability of the Horn of Africa; and lastly, it presents a conclusion and some policy recommendations.

2. Research context

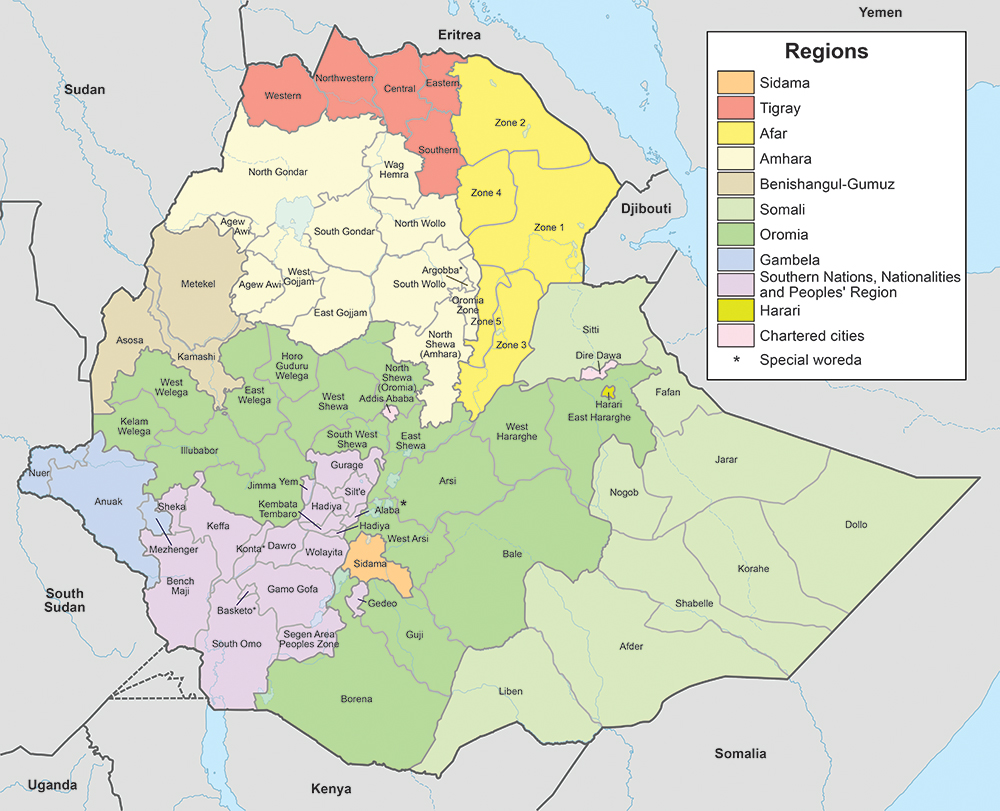

Contemporary Ethiopia (see the map below) is located at the centre of the Horn of Africa and is home to well over 115 million people. Its area of 1.2 million km2 is divided into nine regional states: Tigray, Afar, Amhara, Oromia, Gambella, Benishangul Gumuz, Ethiopia-Somali, Harari, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Regional (SNNPR) States, and two city administrations, viz. Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa (Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia 2010). The names of all regions bear ethno-linguistic identity, except for Gambella and Southern Regional State, to symbolise the post-1991 politics of ethnicity.

Map 1: Political map of Ethiopia

The current ethnic extremism probably has its roots in the pre-1991 nation-state building processes in Ethiopia. It is argued that the failure of the Abyssinian5 elites to share socio-political and economic power with and engage the non-Abyssinians in the nation-state building processes has contributed to the post-1991 unhealthy ethnic relations (Asafa 2004:70; Markakis 2011:35). The pre-1991 nation-state building projects, except for that of the military government (1974‒1991), were founded on the legend of Fetha Nagast (the Law of the Kings) that interwove faith, nation and throne with a mythical past and a prophetic future. Hence, the King was ‘the Elect of God; by virtue of His Imperial Blood… and the anointing He has received, his power was unlimited, unaccountable and unchallengeable’ (see Markakis 2011:33-34). Among them, Menelik II (1889‒1913) whose throne continued until 1930 through Empress Zewditu, Lij Eyasu, and Regent Tefferi, remains a milestone in Ethiopian history. His reign marks the full restoration of imperial authority, its vast territorial expansion and incorporation (Abbink 2011).

During Emperor Haile-Selassie’s regime (1930–1974), Ethiopia acquired in 1931 its first constitution, the gist of which was contained in Article 4 of the revised version of 1955: ‘In the Ethiopian Empire supreme power rests in the hands of the Emperor’: his person was ‘sacred’, his dignity ‘inviolable’, and his power ‘indisputable’. However, the constitution did not properly recognise the multi-ethnic and multi-religious nature of Ethiopian society (Bahru 2002), which was the major factor that led to the emperor’s overthrow by military coup in 1974 (Bahru 2002).

You can find the full paper here.

Source: ACCORD